History knows many events that balance on the edge of myth, faith, and reality. Among them, undoubtedly, one of the most dramatic and discussed is the Ten Plagues of Egypt. This Old Testament narrative, described in the Book of Exodus, has served for centuries as a cornerstone of religious tradition, demonstrating the omnipotence of divine will while simultaneously reflecting the beginning of the Jewish people’s journey to freedom. But what if, behind these terrifying events that befell Ancient Egypt, lies not only a miracle but also a perfectly explainable, albeit incredibly destructive, chain of natural disasters?

The Ten Plagues of Egypt: A View Through the Millennia

Before delving into scientific hypotheses, let’s recall the power and detail with which the biblical narrative describes this miniature apocalypse. These events are not mere natural disasters but a deliberate act intended to break the stubbornness of the mighty Pharaoh and force him to release the Israelite slaves. At the heart of the story lies a confrontation of two mighty wills: the God of Israel, acting through the prophet Moses, and the Egyptian gods, whose power is symbolized by Pharaoh.

The events in question are believed to have occurred during the New Kingdom period, possibly in the 13th century BCE, although precise dating remains a subject of fierce debate among historians and archaeologists. Each of the ten plagues was not just a punishment but a direct challenge to a specific Egyptian deity, giving this conflict a profound theological meaning:

- The First Plague (Blood) – a blow to the god of the Nile, Hapi, and the patron goddess Isis.

- The Ninth Plague (Darkness) – a direct assault on Ra, the sun god, the chief deity in the Egyptian pantheon.

- The Tenth Plague (Death of the Firstborn) – an attack on Pharaoh himself, who was considered a living god.

Our task today is to separate theological meaning from physical reality. Could these catastrophes, as a chain of interconnected ecological events, create the impression of divine intervention? And what conditions in Ancient Egypt made this land so vulnerable?

Ancient Egypt and its Vulnerability: The Context of the Era

To understand why the Ten Plagues were so devastating, it is essential to grasp the role of the Nile River in the life of Ancient Egypt. Egypt, as is well known, is the “gift of the Nile.” The river was not just a source of water but also a transportation artery, a calendar (through its floods), a source of fertility, and, in fact, the foundation of the entire civilization. Any disruption to the Nile’s ecosystem automatically meant the collapse of the state.

Historians and climatologists have long noted that the Mediterranean and the Middle East experienced significant climatic changes during the Late Bronze Age (approximately 1500–1200 BCE), including droughts and possibly shifts in monsoon cycles that affected the sources of the Nile. These changes created a “domino effect,” making the region extremely susceptible to further disasters.

Imagine this: if the Nile’s water level drops or, conversely, rises sharply, it disrupts the natural breeding cycle of insects, provokes stagnant water in floodplain lakes, and, most importantly, jeopardizes the harvest. It is this climatic instability, according to many scientists, that served as the very “powder keg” ignited by the first, most significant plague.

The Prelude: Pharaoh, Prophet, and the Conflict of Wills

Biblical chronology clearly states that the plagues did not begin suddenly. They were preceded by a long period of negotiations and threats. The prophet Moses, who grew up in Pharaoh’s court, returns to Egypt at God’s command to demand the release of his people. Together with his brother Aaron, he appears before Pharaoh (whose name is not mentioned in the Book of Exodus, leading to endless debates about whether it was Thutmose III, Amenhotep II, or Ramesses II).

The key moment is the demonstration of power. When Pharaoh demands a sign, Aaron throws down his staff, and it turns into a serpent. The Egyptian magicians (often referred to as Jannes and Jambres in later traditions) are able to repeat this trick. This shows that the first miracles were within the capabilities of Egyptian magic or illusionism, but the subsequent events, the Plagues, surpassed their abilities.

Pharaoh, convinced of his own divine authority and the power of the Egyptian gods, refuses. This refusal, according to the text, leads to the “hardening of Pharaoh’s heart” and sets in motion the mechanism of the plagues. It is important that the Plagues escalated in their destructiveness and inevitability, which perfectly fits the model of ecological collapse.

Plagues One by One: A Chronicle of the Biblical Narrative

To proceed to a scientific explanation, it is necessary to clearly record the sequence and essence of each of the ten plagues as described in the Book of Exodus (chapters 7–12).

1. Blood (Exodus 7:14–25): The waters of the Nile turn to blood, the fish die, and the water becomes unfit for drinking. This plague lasted seven days.

2. Frogs (Exodus 8:1–15): A huge number of frogs emerge from the Nile and fill the houses, ovens, and even the beds of the Egyptians.

3. Gnats/Lice (Exodus 8:16–19): From the dust of the earth, tiny blood-sucking insects appear, attacking people and livestock. The Egyptian magicians could not replicate this plague.

4. Swarms of Flies (Exodus 8:20–32): An infestation of a vast number of insects. An important distinction: this plague did not affect the land of Goshen, where the Israelites lived.

5. Pestilence on Livestock (Exodus 9:1–7): An epidemic strikes all the livestock of the Egyptians (horses, donkeys, camels, oxen, and sheep). The livestock of the Israelites remain unharmed.

6. Boils and Sores (Exodus 9:8–12): Painful sores and boils appear on people and animals. This plague even struck the magicians, who could no longer stand before Moses.

7. Hail and Fire (Exodus 9:13–35): A terrible hail mixed with fire (lightning) destroys crops, trees, and people in the fields.

8. Locusts (Exodus 10:1–20): An incredible locust infestation that devours everything left after the hail. The land is covered in darkness by the swarms of insects.

9. Darkness (Exodus 10:21–29): A thick, palpable darkness that lasts for three days, again, not penetrating the houses of the Israelites.

10. Death of the Firstborn (Exodus 11:1–12:36): The most terrible plague. In one night, all the firstborn in Egypt die, from the Pharaoh’s firstborn to the firstborn of the slave woman, as well as the firstborn of the livestock.

It is this sequence of events—from water catastrophe to epidemic and climatic shock—that allows scientists to construct a unified, logically connected chain of natural phenomena.

Key Figures: Moses, Pharaoh, and Their Role in the Events

In this drama that unfolded on the banks of the Nile, Moses and Pharaoh act not just as antagonists but as embodiments of two worldviews. Moses is a prophet acting on behalf of an unseen, single God. Pharaoh is the living embodiment of divinity on earth; his power is absolute, and he cannot allow some foreign god to challenge his empire.

Pharaoh’s role in this story is critically important for understanding the narrative. The Bible repeatedly emphasizes that Pharaoh “hardened his heart.” From a historical perspective, any Egyptian ruler facing such a level of catastrophe would immediately turn to his priests and gods. His stubbornness likely reflects not only personal pride but also a theological necessity: if he yielded, it would mean the defeat of the entire Egyptian pantheon.

Moses, on the other hand, acts as a mediator. He does not perform miracles himself; he merely announces them, linking each catastrophe to a specific demand. This “prediction-fulfillment” model is a key element that leads believers to see the plagues as divine intervention rather than blind chance. However, if we look at it from the perspective of crisis psychology, Moses could simply have been a person who perfectly understood the region’s ecological vulnerabilities and knew when and what was likely to happen after the first ecological shock.

Natural Explanations for the Plagues: A Scientific Approach

Can the Ten Plagues be explained without resorting to the supernatural? Today, the most popular and detailed hypothesis links these events to a large-scale ecological cataclysm that could have been caused by one of two factors: either extreme climatic changes in the Nile basin, or, more dramatically, the eruption of the volcano Thera (Santorini) around 1600–1500 BCE on an island in the Aegean Sea.

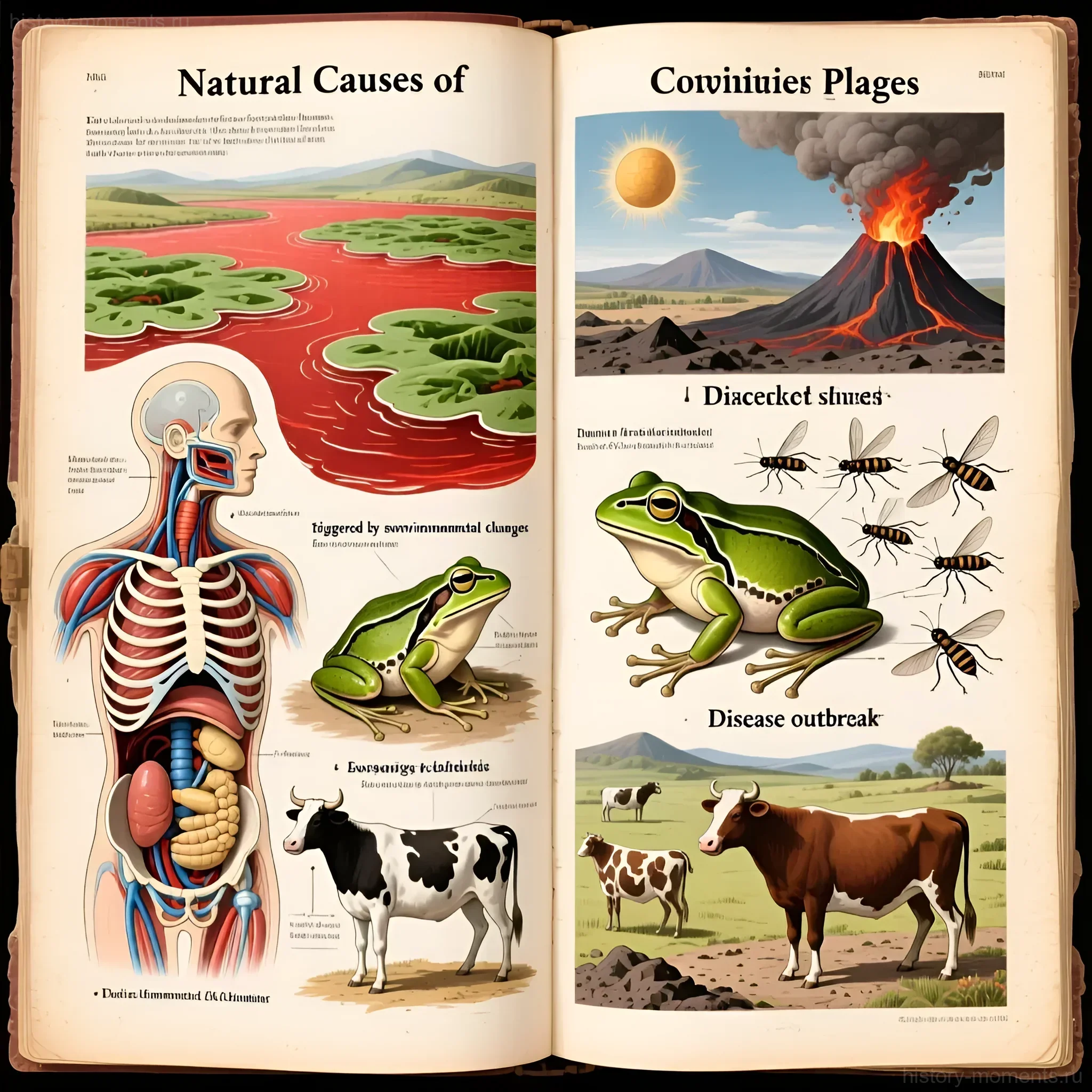

Scientists, including climatologists and microbiologists like John S. Martin, Graham Warren, and Cyril Offer, propose a “chain reaction” theory where each plague logically follows from the previous one:

Plagues 1–3: Water and Biological Shock (Blood, Frogs, Gnats)

Plague 1: Blood. Scientists believe this was a massive bloom of toxic microorganisms, most commonly red algae (e.g., Oscillatoria rubescens) or dinoflagellates. This phenomenon is known as a “red tide” or “bloody bloom.” It occurs when the Nile’s current slows down (due to drought or climatic shifts) and the temperature rises. The algae release toxins that kill fish and give the water a reddish-brown hue. The eruption of Thera could also have contributed by covering the Nile with a layer of red volcanic dust rich in iron.

Plague 2: Frogs. When the Nile’s water becomes toxic and oxygen-depleted due to dead fish and algae, amphibians (toads and frogs) massively leave the river, seeking clean water or escaping onto land. Their sudden appearance in homes is a direct consequence of the Nile’s poisoning.

Plague 3: Gnats/Lice. The death of fish, the mass death of frogs (natural insect predators), and the abundance of decaying organic matter on the banks create an ideal environment for an explosive growth of small blood-sucking insects (mosquitoes, midges, gnats).

Plagues 4–6: Disease Vectors and Epidemics (Flies, Livestock Pestilence, Boils)

Plague 4: Swarms of Flies. An increase in midges and mosquitoes leads to an increase in larger, biting insects that transmit diseases (e.g., horseflies). These insects could have been carriers of diseases that did not directly affect humans but were fatal to livestock.

Plague 5: Pestilence on Livestock. The mass death of livestock (plague, anthrax, or Rift Valley fever) is easily explained by the spread of infection through insect bites (Plague 4). The fact that the livestock of the Israelites in Goshen remained unharmed can be explained geographically: Goshen was located on the periphery, and the epidemic might not have reached there or had different climatic conditions.

Plague 6: Boils and Sores. This plague affects people. It could have been caused by secondary infections related to contact with sick livestock, or, more likely, by the consequences of insect bites carrying a skin infection, such as smallpox or bubonic plague, exacerbated by volcanic ash or airborne toxins.

Plagues 7–9: Climatic Shock (Hail, Locusts, Darkness)

Plague 7: Hail and Fire. This phenomenon is often linked to large-scale climatic anomalies caused by the eruption of Thera. Volcanic ash rising into the atmosphere not only cools the air but also serves as nuclei for moisture condensation, provoking unusually strong and destructive thunderstorms and hail, often accompanied by lightning (fire mixed with hail).

Plague 8: Locusts. Unusual weather conditions (e.g., increased humidity after the hail) and shifts in wind patterns caused by the climatic shock could have led to mass locust migrations from the desert into Egypt. Locusts feed on everything left after the hail, completing the destruction of the harvest.

Plague 9: Darkness. The most convincing natural explanation is either an extremely strong and prolonged sandstorm, the “Khamsin,” which can last up to three days and completely block sunlight, or, more likely, a cloud of volcanic ash (tephra) from the eruption of Thera. The ash settled in the atmosphere could have plunged Egypt into thick, palpable darkness for three days.

Plague 10: Death of the Firstborn

This plague is the most difficult to explain scientifically, as it is selective and instantaneous. However, there are several hypotheses:

- Toxins in Grain: After the hail, locusts, and humidity, grain reserves could have been affected by toxic fungi or mold (e.g., ergot). In Egyptian families, there was a custom whereby firstborn males, as heirs, had the privilege of being the first to receive a portion of food from the new supplies. If this was toxic grain, then the firstborn became the first victims.

- Respiratory Poisoning: The death of firstborn livestock and humans could be linked to the release of poisonous gases (e.g., carbon dioxide) that accumulate in low-lying areas. In Ancient Egypt, firstborn children often slept on the floor or in poorly ventilated rooms, making them more vulnerable to suffocation or sudden death from toxic fumes.

Thus, the scientific approach does not deny the events but explains them as a sequential ecological collapse, where one disaster порождало the next, creating an effect that contemporaries could only perceive as the wrath of the gods.

Interesting Facts About the Ten Plagues of Egypt

Despite their colossal cultural significance, there are many little-known but fascinating details surrounding the story of the plagues:

- Lack of Archaeological Evidence: To date, no direct archaeological evidence has been found to confirm the mass exodus of Israelites from Egypt or the catastrophic destruction corresponding to the plagues, leading to debates about the exact time and scale of the events. Most scientists supporting the natural hypothesis believe the events were localized in the Nile Delta and did not affect all of Egypt.

- The Ipuwer Papyrus: This ancient Egyptian document, possibly dating to the Middle Kingdom (but describing earlier events), contains a description of calamities that befell Egypt: “The river is blood,” “Light has vanished,” “Laughter has disappeared.” Some researchers see in it an Egyptian perspective on a catastrophe similar to the plagues, although others consider it a general description of social chaos.

- Magical Contests: The Bible clearly states that the Egyptian magicians (priests) were able to replicate the first two plagues (turning water into blood and the appearance of frogs). This emphasizes that these two phenomena were perhaps more common or could be imitated using chemistry or illusions, unlike the subsequent plagues, which were too large-scale.

- The Plague of “Death of the Firstborn” and Passover: This final plague is the direct basis for the establishment of the festival of Passover. Jewish families were to mark their doorposts with the blood of a sacrificial lamb so that the Angel of Death would “pass over” (hence the name of the holiday).

Historical Significance and Influence of the Plagues on Culture and Religion

Regardless of whether the Ten Plagues were the result of divine intervention or a chain of ecological disasters, their historical and cultural impact cannot be overstated. This narrative has become fundamental to the three Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Formation of Jewish Identity

The plagues and the subsequent Exodus (departure from Egypt) are the central foundational myth of the Jewish people. They symbolize the transition from slavery to freedom, from polytheism to monotheism, and serve as an eternal reminder of the covenant between God and His people. The annual festival of Passover, celebrated to this day, is a direct reenactment of the events of the Tenth Plague and the Exodus.

Influence on Art and Literature

The story of the plagues has inspired countless works of art, from medieval manuscripts to Renaissance masterpieces and modern cinema (e.g., the 1956 film “The Ten Commandments” starring Charlton Heston). Artists have long sought to convey the visual horror and drama of these events—from the red waters of the Nile to the pitch-black darkness.

A Symbol of Resistance Against Tyranny

In a political and social context, the story of the plagues is often used as a metaphor for the struggle against oppression and tyranny. Moses, challenging the most powerful ruler of his time, has become a symbol of civil disobedience and the pursuit of freedom, making this narrative relevant even today.

Ultimately, scientific explanations do not diminish the power of the story of the plagues. They merely offer us a dual perspective: it was not only a great miracle of faith but also, perhaps, one of the most significant and tragic ecological events ever recorded in human history.

FAQ: Most Frequent Questions About the Ten Plagues of Egypt

We have gathered answers to the most popular questions that arise when studying this incredible story.

In what year did the Ten Plagues occur?The exact date is unknown. Historians propose a wide range, typically dating the events to the period between 1550 and 1200 BCE (the New Kingdom era). The most popular hypotheses link the Exodus to the reigns of Thutmose III, Amenhotep II, or Ramesses II, although archaeological data does not provide a definitive answer.

Why did the plagues only affect the Egyptians and not the Israelites?According to the biblical text, this was a manifestation of divine providence. From the perspective of the natural hypothesis, it could have been related to geographical factors. The Israelites lived in the land of Goshen (presumably, the eastern part of the Nile Delta). Many disasters (e.g., livestock pestilence, insects) might have been localized or less intense in this region due to local climatic conditions or landscape features.

Can the eruption of Thera be considered the sole cause?The eruption of Thera (Santorini) is a powerful factor, but not the only one. It could have triggered climatic shock (hail, darkness) and water acidification. However, the first plagues (blood, frogs) could have been caused by a prolonged drought, a drop in the Nile’s water level, and the growth of toxic algae. Most likely, it was a combination of several factors.

Which plague was the most destructive?In terms of human casualties, the most terrible was undoubtedly the Tenth Plague – the death of the firstborn. In terms of economic and ecological collapse, the most destructive were the Hail (destruction of crops) and the Locusts (devouring of remnants, leading to famine).

Why did Pharaoh not release the people after the first plagues?The Bible explains this by the “hardening of Pharaoh’s heart,” which is sometimes attributed to his pride and sometimes to direct divine action to demonstrate omnipotence. Historians believe that Pharaoh could not release the labor force (Israelites) as it would have led to the collapse of an economy based on slave labor. Yielding to a foreign god would also have meant political suicide.