In today’s world, where books are available in every home, on every shelf, and even in digital form at our fingertips, it’s hard for us to imagine an era when a single book was a treasure accessible only to the select few. Before Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of printing in the mid-15th century, the creation of each volume was a feat of patience, craftsmanship, and significant expense. It was a world where a book was not just a container of information; it was a work of art, a relic, and a symbol of knowledge, power, and even divine presence.

Diving into the Middle Ages, we discover that the concept of a “book” was significantly different from ours. It was not a mass-produced commodity but a unique artifact, each with its own story, its own journey from carefully prepared materials to exquisite binding. Understanding what these manuscripts looked like, what they were made of, who created them, and how, allows us to better appreciate the value of the written word in that distant era and the scale of the cultural revolution brought about by printing.

Before Gutenberg: Why Were Medieval Books Treasures, Not Just Texts?

For a modern person, a book is an everyday item that can be purchased for a relatively small sum or even obtained for free from a library. In the Middle Ages, the situation was entirely different. Books were of incredible value, often comparable to large landholdings, herds of horses, or significant wealth. Historians explain this exceptional value by several key, interconnected factors.

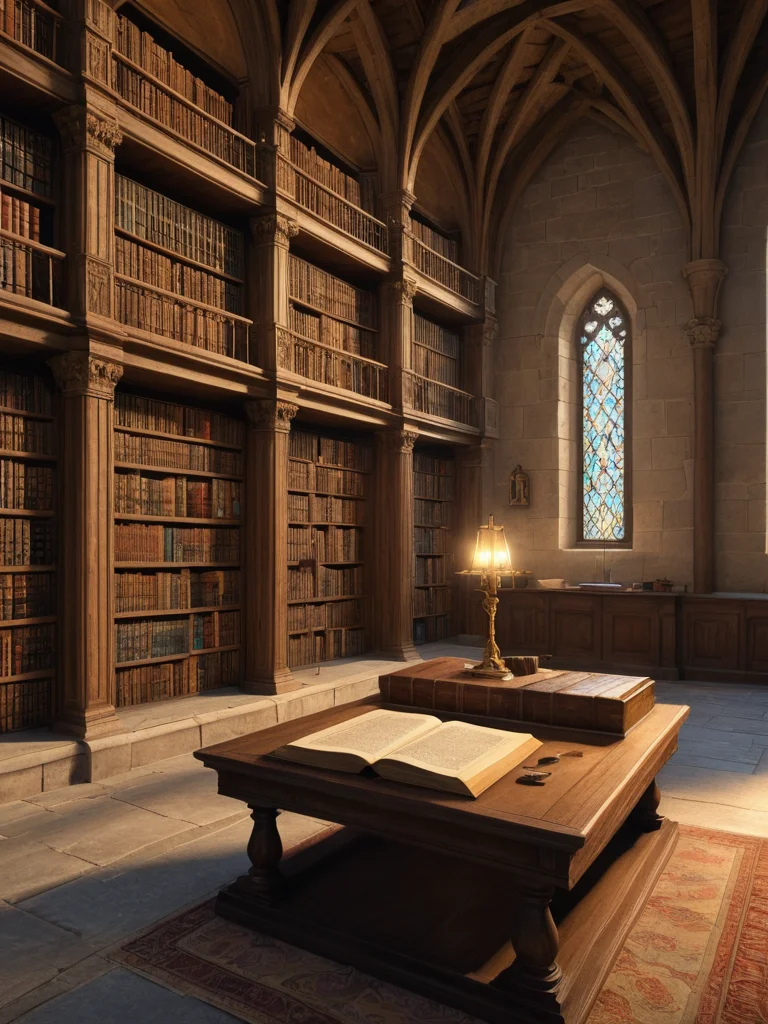

Firstly, their incredible rarity. The number of books in circulation was negligible compared to modern standards. A large monastic library might contain only a few hundred volumes, while university libraries, which appeared later, boasted only slightly more. Imagine a world where each text existed in only a few copies, and each one was unique. This rarity automatically elevated a book to the status of a priceless artifact.

Secondly, the laboriousness and duration of the creation process. Each book was the result of many months, and sometimes many years, of work by a team of highly skilled specialists. It was a long and painstaking process, requiring not only physical effort but also deep knowledge, artistic skills, and immense patience. In an era when there were no machines capable of automating even part of the process, every stage was done by hand, from preparing the parchment to the final stroke of an illustration. This manual labor, of course, made each copy extremely expensive and exclusive.

Thirdly, the cost of materials. As we will see, medieval books were not made from cheap paper. The primary material was parchment, the production of which required a vast number of animal skins—calves, sheep, and goats. Creating just one Bible required the skins of hundreds of animals, and the process of their treatment was complex and costly. In addition to parchment, precious pigments were used for paints, including ultramarine from lapis lazuli, gold, and silver for illuminations, as well as high-quality leather and metal for binding. All these components were expensive and required significant resources.

Finally, symbolic value. In a society where the majority of the population was illiterate and knowledge was transmitted orally, a book was a source of highest wisdom, sacred knowledge, and divine revelation. Most early medieval books were religious texts: Bibles, Psalters, Missals. They were used in liturgy, for personal prayer, and as objects of reverence. Owning a book, especially a beautifully illustrated one, was a sign of high status, piety, and power. Monasteries, which were centers of education and culture, guarded their libraries jealously, as they contained not only texts but the very memory and knowledge of civilization.

Thus, a medieval book was not just a carrier of information but also a work of art, an object of luxury, a symbol of status, and a repository of precious knowledge. Its value was measured not only by the number of words but also by the months of labor, the cost of materials, and the deep spiritual meaning it conveyed. It is no wonder that each of them was a true treasure.

Not Paper, But Skin: What Were Books Actually Made Of in the Middle Ages?

If today we imagine a book as a stack of paper pages in a cover, then in the Middle Ages, such an idea would be fundamentally incorrect. The primary writing material in Europe until the late Middle Ages was not paper, but parchment. This material, possessing amazing durability, played a key role in preserving knowledge for many centuries.

Parchment (from the name of the ancient city of Pergamum, where, according to legend, it was invented or improved) is specially treated animal skin. Most often, calf, sheep, and goat skins were used. The highest quality and most expensive was considered vellum—very thin and smooth parchment made from the skins of young or even unborn calves. It was particularly delicate and suitable for creating luxurious manuscripts with many illustrations.

The process of making parchment was extremely labor-intensive and required high skill. First, animal skins were thoroughly cleaned of wool and flesh residues. Then they were soaked in lime solutions to remove fat and further facilitate cleaning. After that, the skins were stretched on special frames, and the most crucial stage began—scraping. Using special semicircular knives (lunaria), craftsmen carefully removed all irregularities, making the surface as smooth, thin, and uniform as possible. The skins were stretched and scraped until they became perfectly even, suitable for writing on both sides. Finally, the parchment was dried, smoothed with pumice, and, if necessary, bleached with chalk or other substances.

Why parchment and not paper, which was known in China much earlier and reached Europe through the Arab world? Firstly, parchment was incredibly strong and durable. It withstood repeated folding, did not tear, and did not crumble over time, unlike early types of paper. Secondly, its surface was ideal for writing with a quill and applying bright colors, including gold leaf, which adhered well to the smooth surface. Thirdly, parchment was more resistant to moisture and pests, which was critical for preserving valuable texts. And finally, it could be reused. If there was a shortage of material or a need to rewrite a more current text, the old parchment could be scraped off and used for a new inscription, creating so-called palimpsests. This speaks to the extraordinary value of the material.

Paper began to enter Europe in the 12th-13th centuries, but for a long time, it was considered a less prestigious and less durable material, used mainly for drafts, business documents, or less important texts. Only by the 14th-15th centuries, with the development of paper mills, did it become more accessible and gradually begin to displace parchment, paving the way for printing.

Ink, which also differed from modern inks, was used for writing on parchment. The most common were iron gall inks, made from gallnuts (growths on oak trees caused by insects), iron sulfate, and gum arabic. These inks produced a stable black or brownish-black color, which could acquire a rusty hue over time. Red ink, often based on cinnabar or red lead, was used for rubrication (highlighting headings, first letters, and important passages).

The binding of a medieval book was also a true work of art and protection. Pages were assembled into quires, then sewn together. The resulting block was attached to wooden boards covered with leather. The corners of the book were often protected with metal fittings, and heavy metal clasps or straps were used to secure the pages and prevent them from deforming. The most luxurious copies were adorned with precious stones, enamel, ivory, and filigree, further emphasizing their status as treasures.

A Handwritten Miracle: How and Who Created Pages ‘Printed’ by Hand?

The creation of each medieval book was a large-scale project, comparable to the construction of an architectural structure. It was not the work of a single individual but the labor of an entire workshop, where each person performed their specialized role. The main centers of book production in the early and high Middle Ages were monastic scriptoria (from Latin *scriptorium* – place for writing), and later, with the flourishing of universities, secular workshops also emerged.

Imagine a quiet, well-lit room in a monastery, where rows of monk scribes (*scribae*) bent over tables. Their work was extremely monotonous, demanding on eyesight and patience. The process of creating a book began long before the quill touched the parchment.

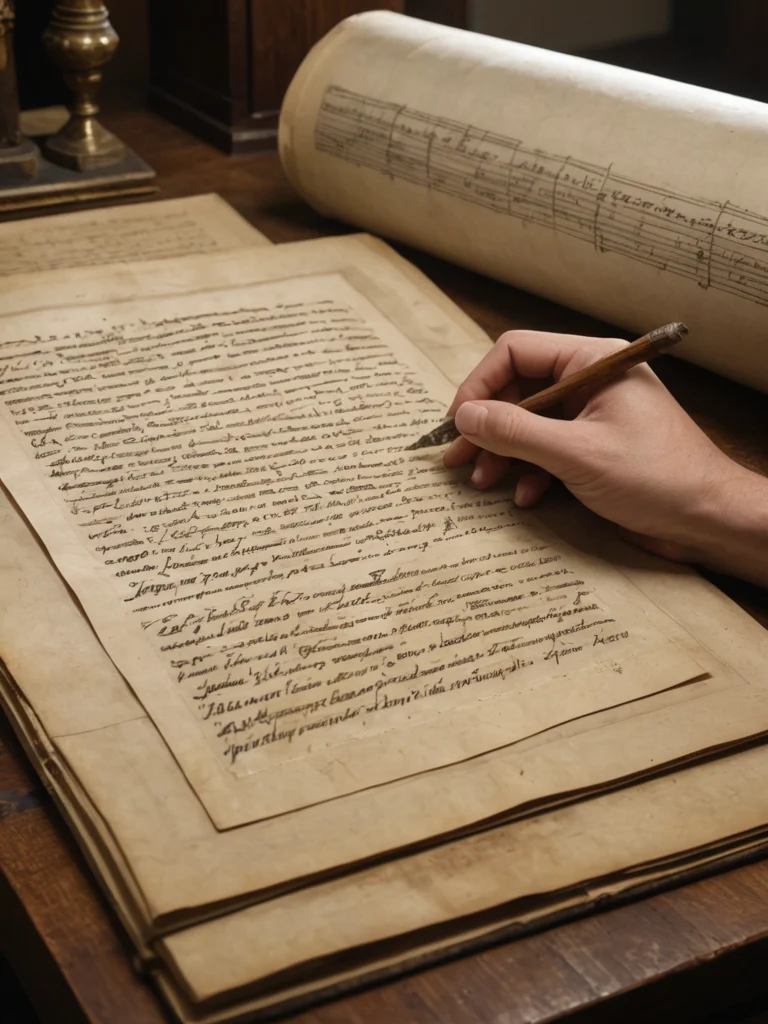

First, the parchment, obtained after all preparatory procedures, was cut into sheets of the required size. Then, these sheets were carefully ruled. Using a ruler, compass, and a sharp object (awl or blunt knife), lines were drawn on each page, indicating margins, the number of lines, and font size. These invisible lines helped the scribe maintain the straightness of the text and uniformity of format, which was important for aesthetics and readability.

The main work of copying the text was done by the scribe (*scriba*). He worked by copying the text from another existing manuscript, called a protograph. This process required not only beautiful and neat handwriting but also deep concentration, as any mistake could lead to a distortion of meaning. Scribes worked for hours on end, often in cold rooms, by the dim light of candles or oil lamps, which greatly affected their eyesight and health. Sometimes the text was copied by dictation, but more often, the scribe worked in silence, transferring words to parchment line by line.

After the main text was copied, the rubricator took over. His task was to add red inscriptions (rubrics, from Latin *ruber* – red), which highlighted headings, the first words of chapters, comments, or important instructions. Red was used to attract attention and structure the text, making it more convenient for reading and navigation. Rubricators might also add simple decorative initials.

The most exciting stage was the creation of illuminations. This was done by illuminators or miniaturists. They transformed the manuscript into a work of art, adding colorful initials, ornamental borders, and full-page illustrations (miniatures), which often depicted biblical or historical scenes, scenes from everyday life, or allegories. For these purposes, a wide variety of expensive pigments were used: blue ultramarine (obtained from lapis lazuli), red cinnabar, green malachite, yellow orpiment, and, of course, precious gold leaf.

The illumination process was multi-stage. First, the artist made a sketch with a pencil or silverpoint. Then, an adhesive (gesso) was applied for the gold, and only then were thin sheets of gold leaf carefully attached and polished to a mirror shine. Only after this were the paints applied, layer by layer, with incredible detail. Illuminators were not just artists but also chemists, knowledgeable about the properties of various pigments and their combinations.

Finally, after all parts of the book were completed, the corrector stepped in, who proofread the text, comparing it with the original and correcting the scribes’ errors. And, finally, the book was handed over to the bookbinder, who assembled the individual sheets into quires, sewed them, and bound them into wooden boards covered with leather. Sometimes, the entire process was overseen by the archivist or librarian (*armarius*), who was also responsible for the preservation and acquisition of the library.

Medieval tools were simple: quills from goose or swan feathers, which needed regular sharpening; inkwells; pumice for smoothing parchment; knives for scraping out errors; rulers and compasses. Nevertheless, with these simple tools, masters created masterpieces that inspire admiration to this day.

Imagine how much time it took to create one such book. A Bible, consisting of hundreds of sheets, could be in production for several years. Each page was a testament to thousands of hours of painstaking work, making these manuscripts not just texts but unique monuments to human diligence and craftsmanship.

From Sacred Texts to the Mysteries of Alchemy: What Was Written and How Were Medieval Manuscripts Decorated?

The content of medieval books was as diverse as life itself in that era, although the thematic distribution differed significantly from modern times. Primarily, manuscripts served the purposes of religion and education, but beyond that, they preserved knowledge in a wide range of fields: from philosophy and law to science and literature. The diversity of content reflected the interests and needs of society, from the clergy and aristocracy to the emerging urban classes.

Religious Texts: The Pillars of Medieval Book Culture

The lion’s share of all manuscripts created were religious texts. These included:

- Bibles: Complete or partial copies of the Holy Scripture, often of enormous size, intended for monastic or cathedral libraries, as well as for church reading.

- Psalters: Books of psalms, often richly illustrated, used for personal prayer and liturgy. They were among the most popular books and were often commissioned for noble individuals.

- Missals and Breviaries: Books containing texts and prayers for divine services.

- Books of Hours: Probably the most common and personal books for laypeople. They contained prayers intended for reading at specific hours of the day, as well as calendars and other devotional texts. Books of Hours were often commissioned by noble ladies and gentlemen and were incredibly richly decorated.

- Lives of Saints: Accounts of the lives and miracles of saints, serving as examples to follow and sources of inspiration.

- Theological Treatises: Works by thinkers such as Augustine of Hippo, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, and others, which formed the foundations of medieval philosophy and theology.

Secular Knowledge: From Antiquity to Chronicles

In addition to religious texts, there were other categories of manuscripts that gained increasing importance over time:

- Classical Texts: Monasteries played a key role in preserving the works of ancient authors—Plato, Aristotle, Virgil, Cicero, Ovid. These texts were copied and studied, forming the intellectual foundation of the European Renaissance.

- Legal Texts: Codes of laws (e.g., the Justinian Code), collections of canon law, as well as various charters and court records were extremely important for the functioning of the state and the church.

- Scientific and Medical Texts: Included herbals (descriptions of medicinal plants), medical treatises, astronomical tables, and alchemical manuscripts. Sometimes they contained detailed illustrations, such as anatomical atlases.

- Literary Works: Various romances (e.g., the Arthurian cycle), epic poems (such as the Song of Roland), lyrics by troubadours and meistersingers, as well as satirical works.

- Historical Chronicles: Records of events, describing the history of kingdoms, dynasties, and important occurrences.

- Textbooks: Grammars, rhetorics, logic treatises used in monastic and university schools.

The Art of Decoration: The World of Illumination

The decoration of medieval manuscripts, or illumination (from Latin *illuminare* – to light up, to illuminate), was an integral part of their creation and gave them additional value and beauty. It was not just decoration but a way of visualizing the text, interpreting it, and sometimes conveying hidden meanings.

- Initials: The first letters of chapters or paragraphs were often richly decorated. They could be decorated (intricate patterns, floral motifs) or historiated (containing narrative scenes or figures of people and animals, sometimes even telling a mini-story related to the text).

- Borders and Frames: The margins of pages were often adorned with intricate ornaments, flowers, plants, and sometimes amusing, and at times grotesque, creatures known as drolleries. These motifs could be both symbolic and purely decorative.

- Miniatures: Full-page or inserted illustrations. They served not only for beauty but also to facilitate understanding of the text, especially for illiterate or semi-literate readers who could “read” the story from the pictures. Miniatures depicted biblical scenes, portraits of saints, historical events, scenes from everyday life, and sometimes even fantasy worlds.

Incredibly expensive materials were used to create these decorations. Gold was applied as leaf (thin sheets) or powder and polished to a shine, making the page literally “glow” (hence the name “illumination”). The palette of colors was rich but limited by available pigments: bright blue ultramarine (from lapis lazuli, imported from Afghanistan), red cinnabar, green malachite, yellow ochres, purple, and others. Illuminators were true masters of their craft, passing down the secrets of their trade from generation to generation.

The styles of decoration evolved throughout the Middle Ages. From geometric and symbolic patterns in the early Middle Ages (e.g., in the Book of Kells) to more naturalistic and detailed depictions of the Gothic period. Masterpieces such as “The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry” demonstrate the pinnacle of this art, astonishing with the richness of colors, the fineness of detail, and the depth of composition.

Thus, medieval manuscripts were not just texts but entire worlds where knowledge, faith, and art intertwined, created to preserve wisdom and celebrate beauty.

Ancient Heritage: Why Are Medieval Books Priceless and How Are They Preserved Today?

Every medieval manuscript that has survived to our day is a priceless testament to the past. Its value is not determined by market price, although it can reach astronomical sums, but by its profound historical, cultural, and artistic significance. These books are not just artifacts; they are living bridges connecting us to a world that no longer exists, offering unique windows into the mentality, beliefs, knowledge, and art of people who lived many centuries ago.

Firstly, their historical value is undeniable. Manuscripts are primary sources of information about the Middle Ages. From them, we learn about events, laws, religious practices, scientific ideas, literary tastes, and even everyday life. Many unique texts have survived solely thanks to these manuscripts, and without them, we would never have learned about many aspects of medieval civilization. Every handwriting, every smudge, every drawing can tell a story about the scribe, the patron, and the time in which the book was created.

Secondly, they represent outstanding works of art and craftsmanship. High-quality parchment manuscripts, especially illuminated ones, are the pinnacle of medieval artistic and craft mastery. They demonstrate incredible detail, the use of complex techniques (e.g., working with gold leaf), and a deep understanding of color and composition. These books are not just carriers of information but also aesthetic objects, comparable to the greatest paintings or architectural structures.

Thirdly, their uniqueness and rarity make them particularly valuable. The number of surviving medieval manuscripts is negligible compared to how many were created, and even more so compared to the number of modern books. Many manuscripts have been lost due to wars, fires, careless storage, or simple decay over time. Each surviving copy is a miracle of survival, all the more valuable because each one is unique, handmade, and has no exact copies.

Understanding this pricelessness, modern generations of scholars and custodians are making colossal efforts to preserve this heritage. The main custodians of medieval manuscripts are the world’s largest libraries and museums:

- The British Library in London, which holds one of the largest collections, including masterpieces such as the Codex Alexandrinus and the Lindisfarne Gospels.

- The Vatican Apostolic Library, housing countless religious and secular texts accumulated over centuries.

- The National Library of France (Bibliothèque Nationale de France) in Paris, a treasure trove of medieval manuscripts, including many Gothic Books of Hours.

- The Bavarian State Library in Munich, known for its collections of German manuscripts.

- Many university libraries, such as those in Oxford, Cambridge, and Heidelberg, also possess significant collections.

The preservation of these fragile artifacts requires strict control over storage conditions. Manuscripts are kept in special storage facilities with controlled temperature and humidity levels to prevent the degradation of parchment and pigments. They are protected from direct light, which can cause fading, and from pests such as insects and mold. Access to originals for researchers is strictly limited, and the use of gloves and special supports is mandatory to minimize physical contact.

One of the most important areas of modern preservation work is digitization. Major libraries worldwide are actively digitizing their collections of medieval manuscripts, creating high-quality digital copies of each page. This makes these priceless treasures accessible to scholars and the general public worldwide, without the need for physical contact with the originals, which significantly reduces the risk of damage. Now, anyone can examine the finest details of illuminations, read texts in ancient languages, and immerse themselves in the world of medieval books without leaving home.

Despite all efforts, medieval books remain fragile and subject to natural aging. Therefore, the work of conservators and restorers continues to ensure their preservation for future generations. Each surviving manuscript is not just a monument; it is a living reminder of how humanity valued and transmitted knowledge in the era before mass printing. They serve not only as a source of information but also as inspiration, demonstrating the boundless dedication and skill of those who dedicated their lives to creating these handwritten wonders.